|

"Sit up"

|

| |

|

On the surface, the works of Irving Marcus and Peter Stegall would seem to have little in common.

Marcus' dreamlike images at b. sakata garo place distorted figures in complex compositions that suggest emotional states.

Stegall's cool geometric abstractions at Bows & Arrows bear no reference to visible reality and seem to be calm and

meditative. What the two artists have in common is a feeling for vibrant, radical color – color that becomes

a thing in itself.

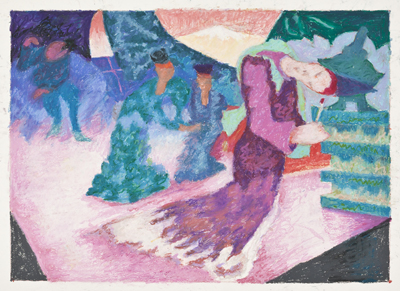

The imagery in Marcus' work is intriguing. In "Sit Up," an oil pastel on paper, two women face each other. One,

a sickly and fragile creature with a pale face, sits up on a bed. The other, dressed as a Japanese geisha, holds

up a cat. On the wall between them is a painting or print of what might be Mount Fuji.

It's a suggestive scene, an intimate encounter between two enigmatic figures, perhaps a patient and healer.

But it is the color that stages the real drama, the brilliant reds, oranges and yellows of the Japanese woman's

kimono, the pale yellow-green of the other woman's skin and the delicate blues and greens of her dress.

Nearby, a large oil painting titled "In Two" gives us another two women – one stretched out on what might be

a rooftop or a tatami mat, the other floating away from her in the sky. It might be a scene of the soul leaving

the body. The red roof and the blues and blue greens of the figure's clothing make a vibrant contrast, as do the

darker pink of the reclining figure's face and the lighter pink of the floating figure's limbs.

In the oil pastel "Incense" we see another female figure, a red-haired woman dressed in tones of mauve

and purple,

who holds up a glowing taper. She is followed by mysterious figures in varying shades of intense blue. Some kind

of ritual seems to be taking place, perhaps a healing one, but again it is the color, so hallucinatory, that draws

us into the scene.

While some of the works in the show are reprises from his exhibit at the Blue Line Gallery last fall, these new

pieces seem to be of a different order. In contrast to the violent color of "Penthouse" and "Scream," there is

a fragility to these that is nonetheless compelling.

Several of the smaller oil pastels exhibit a wacky sense of humor. "King Kong" gives us a small green gorilla

confronted by a large pink human, the whole image flaring like flames. "Queen Elizabeth," with her blue face and

hair, looks like Chairman Mao. "Vision" is a vibrant scene of samurai warriors in a kabuki dance of bold colors.

Stegall's work at Bows & Arrows consists of one large striped painting and several groupings of smaller rectangular

and circular pieces. As they are arranged, they make a strong statement as an installation, the color and shapes

setting up a dance of sorts.

of geometric shapes and close-keyed brilliant colors, are eye candy of the highest order. They wake your eyes up

with sizzling vibrations and halations. In one work, Stegall places triangular shapes in lavender, gray and green

in scintillating relationships that make your eyes literally jump.

On the opposing wall, he places a large, door-size panel of stripes at the center, its tones of pure, intense

color – green, blue, navy, and blue-green – jumping out at you. Around this large piece, he has scattered rectangular

and circular "objects" in quirky arrangements.

The circular objects, which have three dimensions, are a new wrinkle for Stegall, at least new to me, and they have

a quixotic quality that is appealingly wacky. Equally compelling are groupings of small stripe paintings as intense,

despite their small size, as anything by Kenneth Noland or the Washington, D.C., stripe painters of the 1960s.

Bows & Arrows is an unusual venue for an art gallery. Divided roughly into three sections, it houses a clothing

store and a cafe, which often presents live music. Sandwiched in between are two bare walls for hanging artwork.

Stegall's work is so strong that it holds up to what might otherwise be distracting surroundings.

Irving Marcus

WHEN: Noon-6 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday, through March 2

WHERE: b. sakata garo, 923 20th St.

ADMISSION: Free

INFORMATION: (916) 447-4276. www.bsakatagaro.com