|

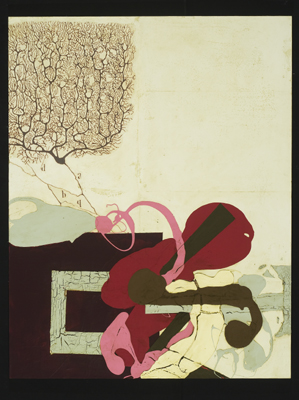

Katherine Sherwood, "Transports Instantaneously, 2007", mixed media on canvas, 72" x 72", 2007.

|

| |

|

Much has been written about Katherine Sherwoods's recovery from a cerebral hemorhage that debilitated the left side of her

brain and paralyzed the right half of her body. The event, which occurred in 1997, forced her not only to relearn language

and basic motor skills, but also to paint with her left hand. While the story of her rehabilitation feeds our thirst for heroic

reinvention and fuels the myth of disability as a door to enhanced perception and self-knowledge, it also seems to have obscured

what makes Sherwood's art so compelling.

This compact show of eight large-and small=scle works from 2006 to 2008, Sherwood, in what amounts to a visual roman á clef,

demonstrated why she is one of the most important painters working today. At first glance,...appears to be tilling the now-familiar

soil of biomorphic abstraction; but her forms are so uniquely stylized that they can't really be compared to any of the

biologically based formulations we've seen in this genre. Sherwood's work is sui generis. One reason is that her every

painted line is derived from a seventeenth-century text containing images knows as Solomon Seals--symbols that the biblical

King devised to summon spirits and extract wisdom. In Sherwood's hands, these forms appear not as stamps, insignia or crests, but

as highly controlled paint pours. They puddle and crack and then tapper off into thin, loopy lines that recall both Franz Kline's

architectonic geometries and Jackson Pollock's late-period flirtation with figure-like forms; which is to say, they rivet the eye

in a way that makes them elegantly iconic.

Sherwood also photo transfers to almost every canvas angiograms of her own brain, which, contrary to what you might expect, look like

the veins of aquatic plants or exotic trees. She also transfers more easly recognizabel images of the cerebral cortex from

sixteenth-century medical texts. Typically, Sherwood also includes strong horizontal lines painted atop interlocking geometric

blocks. Combined, these elements ignite a visual dynamic that blurs the distinction between representation and abstraction, since

much of what appears to be abstract in her pictures is really photo documentation of scientific fact. As is her trademark,

plastic activity, rendered in what she calls "ugly colors," takes place off-center, against mostly neutral grounds--either

cream-colored, paye yellow, ochre or pea-green.

the most powerful example of these oppositional forces shows up in Firmer Spirit, a 42-by-36 inch print in which paint poured

in the shape of a loosely caricatured face, floats atop a cyan-hued tangle of brain matter framed by two orange geometric boxes.

This visage appears to be staring at an unseen point beyond the picture like a leering mask, mocking the hubris of an artist (or a

viewer) who thinks she can one-up nature by creating abstract shapes that are more compelling than the microscopic forms that

reside inside her own skull! I doubt that Sherwood entertained this thought, but the picture certainly lends itself to such

interpretations.

On the other hand, by coupling digital representations of the body with man-made symbols of magical conjuring that have been

manipulated beyond recognition, Sherwood is keenly aware of the common ground shared by art and science in their quest to explain

the forces that animate the human spirit. The results, as seen in the picture on view here, feel a lot like puzzles. They

challenge you to consider (and confront) the very nature of consciousness, and by extension, the abyss of mortality.

Transports Instantaneously, a 72-by-72 inch canvas, uses the shape of a cross as a portal through which you view images

of the artist's angiograms overlaid by biomorphic blobs that look like cross sections of brain matter. These appear in quadrants

of a window framed by a lava-like flows of navy-blue paint that open out onto looping ovoid gestures. Cajal's Revenge, a medium-

sized painting named for an early twentieth-century brain researcher, unfolds with a similar dynamic. It juxtaposes the tree-like

shape of an angiogram in the top left corner with an acretion of multicolored, cracked paint spills that fills the picture's bottom

half and resembles an exposed archaeological dig seen from the air. Thin lines connecting the two halves suggest the fragile link

between body and brain.

In only one work in this exhibition, Hush, Hush, a 38-by-30-inch print, does Sherwood depict one of the seals realistically.

It's a circular shape whose interior froms recall the medieval motifs that show up frequently these days in pattern and decoration.

And while it's instructive and interesting to see Sherwood's source material unfiltered, the image, even those offset by other,

more lyrical shapes, makes the picture feel diminished in comparison to her richly hued, highly textured canvases.

If a recent painting, Body Bingo, is any indication of a trend, Sherood may be starting to express herself more economically.

This 48-by-60-inch canvas is dominated by two dark puddles of paint that sit at the bottom center. Running up the left side are three

horizontal bands topped by another of those orange boxes. Higher up, Sherwood superimposes a calligraphic shape over a bingo board

and a small swathc of an angiogram, which here looks like anX-ray printed as a cyanotype. The painting, like so many in Sherwood's

oeuvre, is an enigma--one you can't stop look at.

Part of what makes her work so alluring is the sheer number of styles what coalesce; gestural and geometric abstraction, photograph,

minimualism and color field painting. Sherwood maintains she hasn't studied or employed these styles in a conscious manner, but

instead arrived a pictorial conclusions through a laborious trial-and-error process. In the end, there's a fierce compositional

logic at work in these paintings, and it exerts an almost vertiginous pull, brining viewers face to face with Sherwood's obession

with the brain's mysteries.

Her paintings and prints don't do much to explain those mysteries; Sherwood isn't much interested in illustrating medical science,

only in amplifying the mysteries and casting them in shaper relief.