Victor Wong leaves the movie business for a new role -- husband and artist

By Dixie Reid

Bee Staff Writer

(Published Feb. 10, 2001)

It was nearly 10 years ago that Victor Wong walked the dry-dirt streets of a crumbling Delta town and contemplated life. His life.

"I don't think I'll ever make it big in Hollywood," he said. "There have been three wars in Asia and when they look at an Asian man, he is still the enemy. He'll never be the hero."

The good news is that he is still the same funny, insightful man - and has never been happier. He is married for the fourth time, has come back to live in his beloved Sacramento River Delta and has resumed his passion to be an artist. The Sacramento gallery b. sakata garo currently is showing 28 of his computer-generated paintings, which sell for up to $800. Wong will attend a reception at the gallery this evening.

He remembered what he'd said 10 years ago about his need to perform. He rubbed his face. "I was old enough to retire. I know that I can't do it."

Even as he was pursuing art, Wong found that acting was never far from his heart. But he never bothered to take acting lessons.

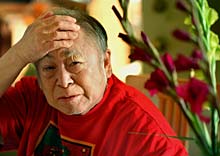

Victor Wong, who appeared in more than two dozen movies, has stopped his acting career as a result of health problems. He now creates computer-generated paintings, which fetch up to $800.

Bee/Leilani Hu

Back then, at age 63, Wong had worked in the movies for six years. Hollywood seemed to love what he laughingly called his "lopsided" face - caused by a midlife onset of Bell's palsy - and his gentle manner. Even though he was never the leading man, he received supporting roles in major motion pictures: "The Joy Luck Club," "The Last Emperor," "Big Trouble in Little China," "The Golden Child" and "Tremors."

Wong said something else that day in 1991 that rings now with particular poignancy: "If I can't act, I go crazy. I need it every day."

Sadly, those days are over. Wong suffered two strokes in two years, leaving him struggling to speak and reliant on a walker or wheelchair.

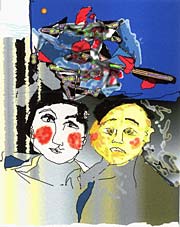

"!Blindst" is one of Wong's creations. "I'm very thankful I'm here by the river where it's quiet," said Wong, who lives on Andrus Island in the Delta. "It is like the south of France, where van Gogh lived."

"My determination was to get back to, I wouldn't say normal, but to function as a human being, so I turned to art as the only thing I could do," Wong said last week. He sat at the kitchen table in his small, rented house on Andrus Island, a few miles outside Walnut Grove. The river runs nearby, on the other side of the levee road, and behind the house a vineyard lies fallow and a fig tree is putting on its spring buds.

"I'm very thankful I'm here by the river where it's quiet," Wong said. "It is like the

south of France, where van Gogh lived."

His wife, Dawn Rose, puttered in the kitchen, brewing a pot of green tea and fussing over him.

"I learned how to talk again and move about," Wong said, laboring to make his words intelligible. "If not for her, I would not be able to get going. I couldn't walk or talk. I was paralyzed on one side."

She walked over to his side. "He had lots of physical therapy," she said, "and is very persistent. He's got amazing patience. He's an inspiration."

She kissed her fingers and touched the top of his head. He squeezed her hand.

They met about 15 years ago, became friends and corresponded by e-mail for a long time. She is an artist with a studio in Locke, the very town Wong walked through in 1991 while thinking about acting.

They married three years ago, living for a while in her studio before renting this house. They want to buy it, but the owner insists on selling the house in tandem with the adjacent trailer park. Instead, they bought a 1913 storefront in Walnut Grove, a one-time chop-suey house they hope to reopen this summer as an art gallery and teahouse. They may call it Tin Bo ("heaven-blessed" in Chinese). It's likely they would live on the property.

Dawn blew her husband a kiss, promised to return soon and left to do errands. He watched her walk out the door.

Victor Wong stands before one of his artworks in his home, near Walnut Grove.

Bee/Leilani Hu

Wong has made 28 movies, starting with "Dim Sum: A Little Bit of Heart" in 1984 and ending with "3 Ninjas: High Noon at Mega Mountain" in 1998.

"There weren't many Chinese American actors," he said. "They needed good acting with an old Chinese man, so I took the parts. I was able to be at the right time in the right place. I was lucky to get the parts I did. I was lucky to be where the needs were. The needs are not always there."

He has been performing since childhood. Wong was born in San Francisco and moved with his family to the Delta town of Courtland, near Locke, when he was 3. His parents were hired to open a school for the children of Chinese laborers and farmers. They returned to San Francisco three years later.

Wong's father was prominent in the city's Chinatown, serving for many years as its mayor. He wanted his son to become a scholar, perhaps a politician, but the son wanted to be an artist.

Wong's first art show was at City Lights, Lawrence Ferlinghetti's bookstore not far from the gates of Chinatown. Wong befriended the poet Ferlinghetti and other members of the Beat generation who flocked to him, including Jack Kerouac.

Once, when they all went to Big Sur on a retreat, Wong documented the event by making felt-tip-pen sketches.

"Rain Rain" is another of Wong's paintings.

Bee/Leilani Hu

"I could just act," he said, shrugging. "Acting is a part of me."

He did some community theater work and, one night, a Hollywood director was in the audience. Wong landed a role in the 1984 TV movie "Nightsongs" and then the feature film "Dim Sum." After that, he barely caught his breath between movies.

"I never auditioned. My pictures were auditions," he said.

He lived in Sacramento with a girlfriend who operated a midtown day-care center.

"To live in Hollywood is to be boxed into a company town, to be conforming to certain conformities," he said. "I needed fresh air. I couldn't be put in a small little tiny house with the doors locked. My agent could tell them (movie directors) where I was."

It was a long time before Wong's father went to see his movies. "His friends saw me in a movie, and they had to drag him into the theater. He said I was very good."

Wong stopped speaking when a cough rattled his chest. He wiped his eyes with a paper towel. "I like acting because I could be other than myself. I could absorb into another person and become that person. It becomes a compulsion. I have to do it."

But now that he no longer can?

He shrugged. "It comes out in my art."

He pushed back the kitchen chair and grabbed his three-wheel walker, leading the way to his bedroom. His computer sits in front of the window that overlooks the vineyard and levee road.

"I'm reading 'Harry Potter.' For the second time. I love it," he volunteers. Asked which one he's reading, he said, "All of 'em."

He revved up the computer, an NEC MultiSync outfitted with "paint program" software. He draws with the mouse, using it like the dials on an Etch A Sketch, and fills in with colorful "paint." His art, which is cartoony, colorful, humorous and busy, is, he said, "like Chagall, and it's me."

He returned to his spot at the kitchen table.

If he gets out at all, it's usually to see his doctors or to spend a little time at a bird sanctuary, observing migratory wildlife. When he's at home, he likes to think and meditate.

"This is a good time of life," he said, "especially with Dawn. I'm so glad I found her. I have been alone a lot of my life, being an artist and an actor. It's good to retire, because I stopped trying to do things. I let them come to me."